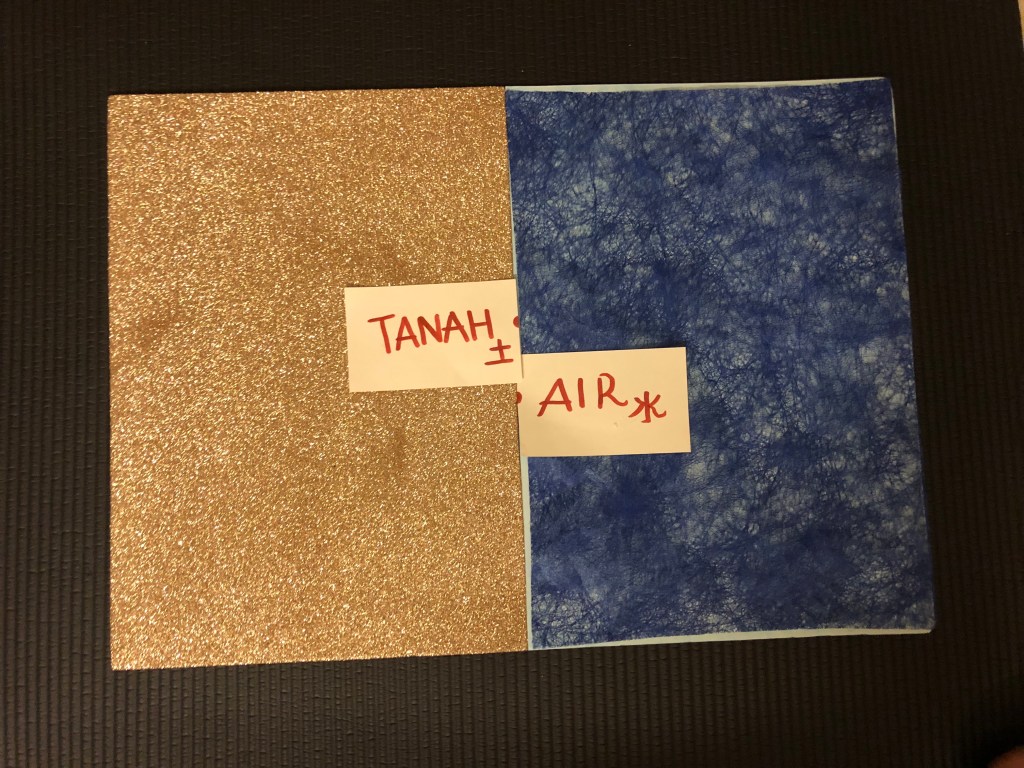

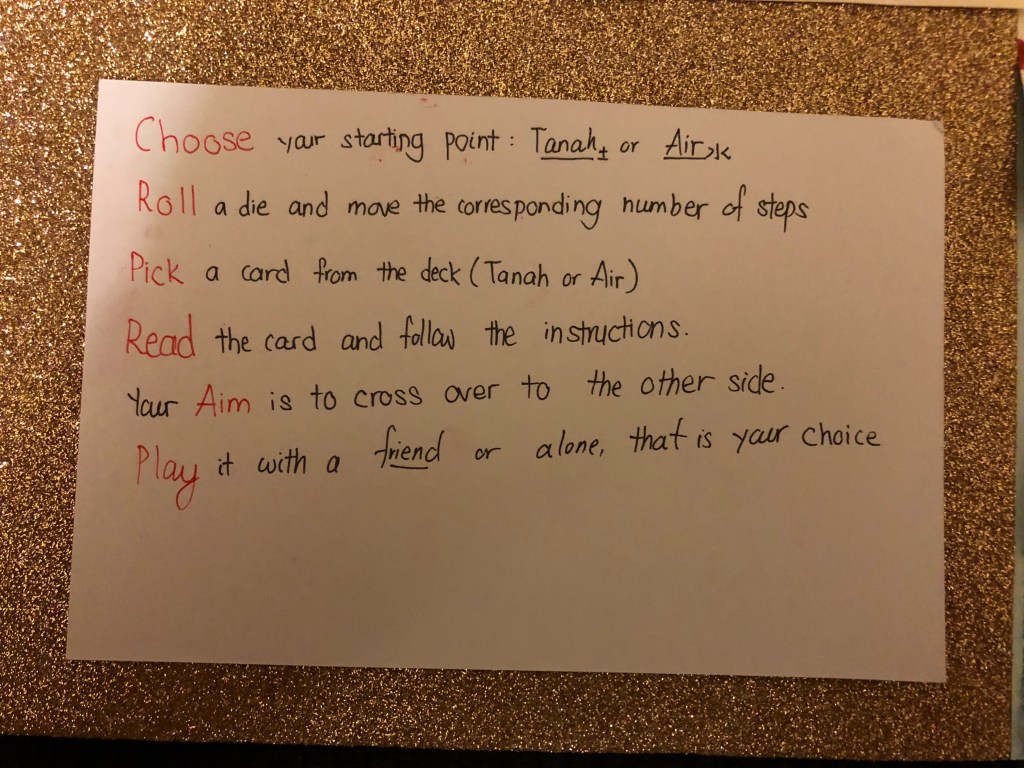

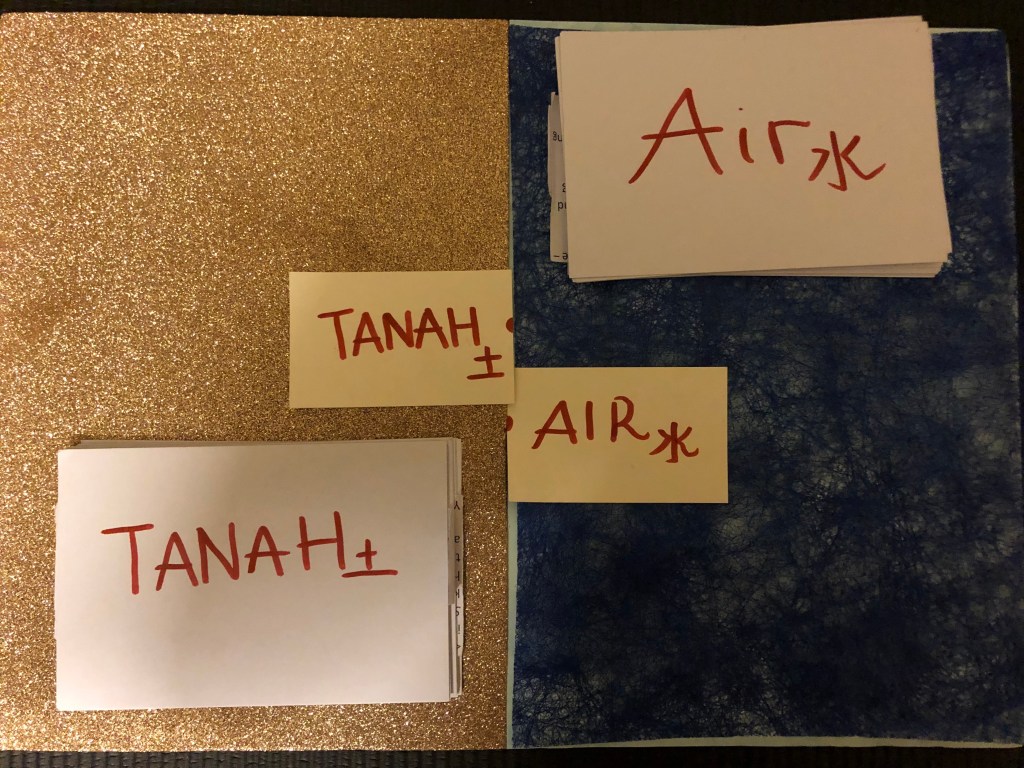

The idea came to me in a dream after watching Tanah • Air. The original idea is to create a cross between Monopoly and Snakes and Ladders, with the board divided into two – Tanah and Air. It is meant for two to four players, but it could work with one. The game was originally meant to have the players attempt to “cross” over to the other side and when they stop on specific squares, they have to draw a card and follow the instructions. There will be slides and ladders that impede or help the players. It is hoped that the players will never be able cross over, and is stuck oscillating within their side of the board, but if they do cross, they are thrown into “Jail”. I wanted to explore the futility of returning “home”, and in a way, explore how we are too, complicit in this marginalization.

Due to time constrains and limitations of skill, the end-product ended up being wildly different from what I initially hoped for. It is a simplified version that excessively played up futility of progress, and gave the game away too early.

Tanah

<The storyteller sits and conjures figures from the past, spirits that haunt you. The spirits are in front of you, cloaked in black. Sometimes, they are in red. Sometimes, they overthrow platforms. Sometimes, they drink from a clay jug. Sometimes, they pour water over themselves, each other. Sometimes, they pull at each other, lunge at each other, tear at each other. You sit, and you watch, and you listen.

You move three steps back>

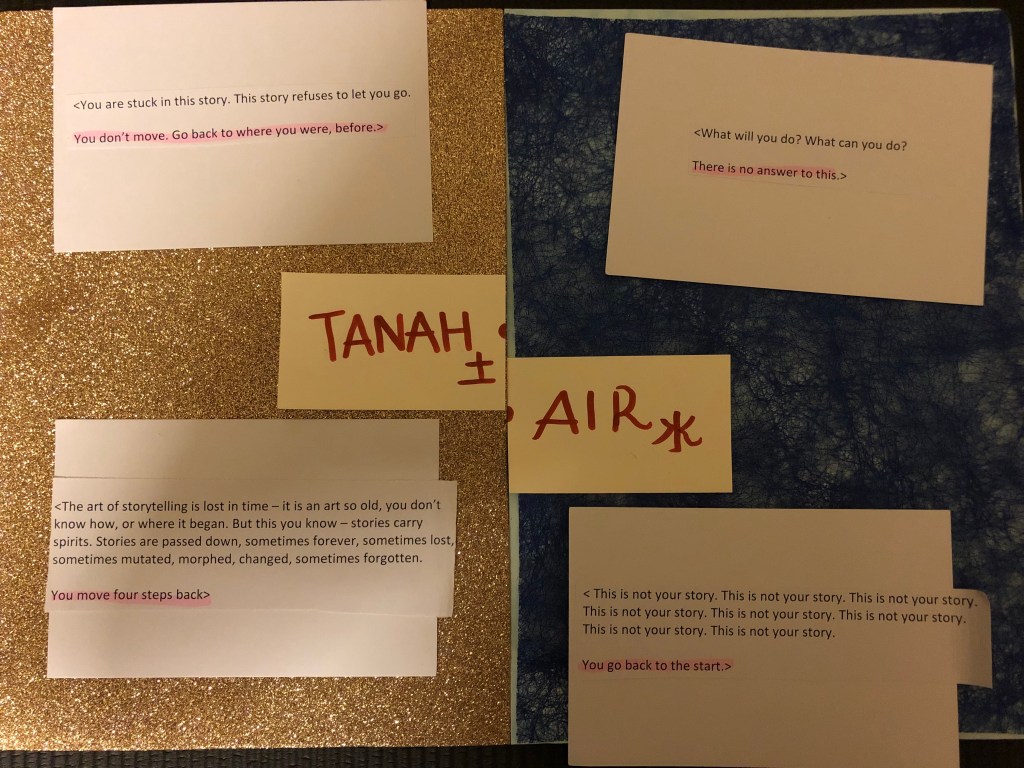

<The art of storytelling is lost in time – it is an art so old, you don’t know how, or where, it began. But this you know – stories carry spirits. Stories are passed down, sometimes forever, sometimes lost, sometimes mutated, morphed, changed, sometimes forgotten.

You move four steps back>

<The Story of Marmah is part fictional, part fact, a creative re-imagination of history, if you will. Tanah is about the discovery The Story of Marmah, which is born from the re-imagination of Isa Kamari’s 1819 and bits and parts from history. Tanah tears down the history you are taught about in school. It grabs our history back from the hands of our colonisers. This is the story about the people. This is a story about a girl. This is a repossession.

You take one step forward>

<There is a hybrid of movements – Chinese martial arts, silat, Malay wedding processions, breakdance, and many more you lack the knowledge to name. The actors move with strength and fluidity, and you see how their bodies carry the weight of the music and poetic language of the story.

You watch them each carry a red cloth with ceremonial precision and drape a red cloth over their faces. You watch them carry a painfully long bamboo pole. You watch them chase each other in a playful game like lovers, young lovers. You watch them push, crawl, drink, tumble. You watch them carry out a procession, cheering, celebrating, as the Storyteller speaks about violence and grief.

You can’t tear your eyes away, even when you get lost in the Chinese narration.

You move two steps back.>

<The live music has put you in a trance. The performer musician sits next to the storyteller and paints a picture with his music. He creates a soundscape that feels like a world, a reality on its own. You get lost in the world.

You take two steps back.>

<You are stuck in this story. This story refuses to let you go.

You don’t move. Go back to where you were, before.>

< “大海不属于我们//我们属于大海

The sea doesn’t belong to us // We belong to the sea.”

But you are not at sea.

You move seven steps back.>

<What is home? Where do we belong? Why are we so obsessed with belongings – where we belong, what we have, possess. Why do we take and take and take?

You move four steps back.>

<The sea is selfless. We are selfish.

You cannot move. Go back to where you were, before.>

<The colonisers tore down our history and we have forgotten.

Singapore is progressing at a rate far quicker than we can remember.

If we forget the stories of the people, of the land, of the sea, we will forget everything. The spirits disappear. We disappear.

You go back to the start.>

Air

<This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story. This is not your story.

You go back to the start.>

<Air is a verbatim piece, drawing from the interviews with the Orang Seletar community. In an interview with Nabilah Said on ArtsEquator, co-directors Wan Ching and Adib , as well as sound designer Bani, talked about their journey and problems faced while creating Tanah · Air.

Adib said, “the idea is not to become these Orang Seletar onstage, because we are not them… We found a middle ground of showing how the actor, as a Malay Singaporean performer, comes into the space and tries to access the character, before taking on these voices and sharing these stories.”

Air is a collection of stories, experiences, voices that have to be heard.

You take one step forward.>

<A mother is mourning the death of her child. The grief is palpable. It is thick. Viscous. And you think you could drown in this. She is begging for someone – anyone to save her child. She talks about clutching an amulet. She speaks of a name she didn’t have a word for – Jesus. This small, unexpected faith. Her baby is gone. Her child is gone. The actor crumbles, her body heavy with grief. You choke on the grief. You wonder – what could be done?

You go back six steps.>

<Something is pouring. It is looks like a cross between chalk and sand. It is falling onto the head of an actor. His hair is turning white – like snow, like ashes, like sand, like chalk, like everything and nothing at once. It is at once gorgeous and painful to watch. You almost feel the sand-chalk on your skin. On your tongue. The actor speaks about his land – the burial land of his people being stolen, excavated by developers. He is being buried alive. He is being reclaimed. You hear his anger. You hear his resentment. You watch.

You go back five steps.>

<You are on their stage. You watch them draw a map of Singapore – the Singapore they know – with chalk. It looks like a museum exhibition, with artefacts. There is a knife, a glass filled with an orange liquid, a thick file and a video recorder. A screen at one end of the stage is playing a video of the Orang Seletar people hunting crabs.

You watch an actor try and write “Harbour Front” on the floor using chalk. He pauses at ‘b’, thinking. He writes “our”. He erases it. He pauses. Thinks. He tries to write again. He gives up. Moves on.

You go back to where you were before, back to your seat.>

<The actors are still, standing on the cubes that once held their items. Now, they look like artefacts, frozen in time. The screens are showing photos that the Orang Seletar took. You cannot breathe. The photos capture Singapore’s cityline – a land they can no longer access, a land they are banished from.

You are part of that land. You are part of that land. You are part of that land.

You go back to the start of the board.>

<This time, you are acutely aware that you are complicit. You are complicit in forgetting. You are complicit in erasing them. You are complicit in ignoring their voices. You are complicit in not respecting them. You are complicit.

You take ten steps back.>

<Air forces you, the audience to confront indigenous rights – something that we don’t talk about in Singapore. It leaves you with more questions than answers – what can we do? You leave with a sense of guilt you do not know how to make sense of.

What does the Orang Seletar community think of this? How do they feel when they watch us grapple with their experiences?

You don’t know what to do.>

<They speak of their language – the Kon language. It is not Malay – it is far from that. It is theirs. The actors talk about the Orang Seletar’s songs, their stories, their spiritualities – these things that they hold close to their hearts, these things they cannot forget. These things still sound a tad foreign in their lips. Maybe that is the point – the Malay actors from Singapore are not the Orang Seletar.

The Orang Seletar say that their songs are full of spirits. They are full of spirit.

You take a step forward.>

<You hear them talk about the split of Malaysia and Singapore that left them stranded. They did not know. Those who were in Johor had to remain there, and those that were in Singapore that to stay there too. Now, they are unable to fish at Singapore waters, or they risk getting caught. Singapore has exiled them.

You take three steps back.>

<Many of them have converted to Islam, or married Chinese people. Their children attend school on land for an education, to learn how to write and read. But they are excluded. They are othered.

“If we move to land we lose our culture, identity”

“Don’t forget.” Don’t forget.

You return to the start.>

<What will you do? What can you do?

There is no answer to this.>